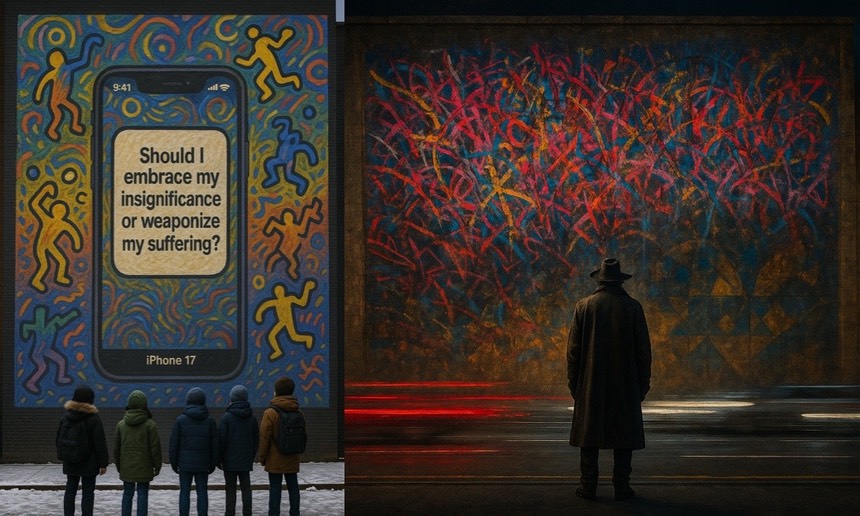

Brooklyn, NY (December 2, 2024) – I used to sit in the same dark place as everyone else, watching what I thought was the whole story. But one day, I found a way out and saw there was more—more truth, more light, more life. Ever since, I’ve been trying to help others find that same path out. I leave little clues and share what I’ve learned through my writing. But most people don’t take it the way I hope. They think I’m trying to act better than them. I’m not. I’m just someone who used to believe what they still believe. And while I understand their reactions—especially in places like the Bronx and other cities where survival sometimes comes before reflection—it still stings.

By advocating for self-confrontation in my writings, I’m not trying to be a jerk. I’m trying to help. I know my tone can feel sharp and my style can be off-putting, especially when I challenge comfort. But that discomfort is part of the process. I’m not trying to be right. I’m trying to be useful. I’m not trying to be liked. I’m trying to be understood. I’m not better than anyone—I’m just trying to be better than I was yesterday. I’m not trying to divide. I’m trying to tell the truth as I see it, even if that truth makes people uncomfortable. That part is non-negotiable.

Still, I’ve learned that being soft and being strong aren’t opposites—they’re both necessary. My greatest gift might be knowing when to stand my ground and when to listen, even when the people I want to help can’t—or won’t—be vulnerable with me. I’m not here to hand out easy answers. I’m here to ask harder questions. Not because I enjoy making people uncomfortable, but because I believe we’re capable of more. And if I seem relentless, it’s only because I know what’s possible when we stop watching shadows and start seeing ourselves clearly.

I love my family, even when we don’t see eye to eye politically. My brother and I are on opposite sides of the political spectrum, but we’ve learned to respect each other’s views and find common ground. This article is for those who, like us, want to bridge the divide and focus on what unites us rather than what tears us apart.

When you look closely at the American Dream, you start to see that it's not just about hard work leading to success. For many, it’s also a story filled with unmet expectations and disillusionment. We are told if we work hard, we’ll get ahead, but for many people, the reality doesn’t match that promise. That disappointment can turn into frustration and division. This article is an attempt to shine a light on how our experiences shape what we believe, and how we might begin to understand each other better if we start with empathy.

For me, writing used to be about trying to change other people’s minds. Now, it’s more about understanding my own. A man once walked into my juice bar and asked about kale. After my well-rehearsed spiel, he asked, “Do you believe in what you’re selling, or are you trying to get me to believe in you?” That moment stuck with me. It wasn’t about vegetables. It was about how much of my life I spent performing certainty—trying to look like I had everything figured out, when inside, I was still searching.

This made me realize that sometimes I’ve done the same thing to others—especially public figures like Donald Trump. I disagree with his politics, but I now recognize that I made him into a symbol of everything I stood against. That made it easier to feel morally superior, but it also meant I wasn't really seeing him as a human being. And if I believe in empathy and complexity, I have to practice those values even when it’s uncomfortable. So, Mr. Trump, this isn’t an endorsement. It’s an apology—for simplifying you to feel better about myself.

We all play roles in a world obsessed with appearances. Trump embraces the performance, while I used to think I was above it—only to realize I was acting too.

Earlier in my life, I thought if I just explained things clearly, others would see the truth. I imagined the world like a beach where people build sandcastles. Some build elaborate ones, believing they’ll last. But then the ocean (life, reality) washes them away. I used to believe my job was to warn people that the waves were coming. Now, I see my role more like someone leaving behind seashells—small reminders that might help others build better when they’re ready.

That shift in perspective came from both personal experience and reading thinkers like Albert Camus, who believed that even when life feels absurd, we can find meaning by choosing to keep going. Camus told a story about Sisyphus, a man from Greek mythology condemned to push a boulder uphill for eternity. It always rolled back down, but Camus suggested that Sisyphus could still be happy—not because of success, but because of his attitude. Even in the struggle, there can be purpose.

Viktor Frankl, a psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor, echoed this idea. He noticed that even in concentration camps, humor and hope gave people strength. Sometimes just finding a reason to laugh, even briefly, was an act of survival. That resonated with me. Humor doesn’t solve everything, but it helps us carry the weight.

Some days, I look at the world and it feels like nothing is real anymore—that we’re just acting out simulations of what life is supposed to be, surrounded by images and ideas that have lost their original meaning. Everything feels like a copy of a copy, and I can’t help but wonder if we’ve lost touch with anything authentic. Other days, I feel an overwhelming sense that everything, even the mess, is unfolding as it must—that despite the chaos, there is harmony hidden underneath, a perfect order I just can’t fully grasp. And then there are days when I wrestle with the belief that the world should be fair, that goodness should be rewarded and cruelty punished. It’s a comforting belief, but I know it doesn’t always hold up. Life often doesn’t match the script we think it should follow.

As I kept reflecting, I realized I had blind spots too. Reading Naomi Klein helped me see how history often repeats itself. In her book Doppelganger, she shows how even terrible regimes, like the Nazis, borrowed their ideas from earlier atrocities committed by so-called "civilized" nations. Hitler admired how the U.S. had treated Native Americans—seeing it as a model. That kind of historical truth is hard to face, but if we ignore it, we’re more likely to repeat it. Klein's message is that we all have to confront the darker parts of our shared past if we want to build a better future.

So why do we avoid these hard truths? Philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer believed that people often run away from uncomfortable thoughts. He said we prefer distractions to reflection. I think he was right. I learned this myself during long periods of loneliness growing up, especially without my father around. Those moments, while painful, forced me to get to know myself.

Another thinker, Blaise Pascal, once wrote that most of humanity’s problems come from our inability to sit quietly in a room alone. He believed solitude could lead to clarity, but today we’re surrounded by distractions—social media, shopping, gambling. Celebrities like Kim Kardashian and Ronaldo promote lifestyles that keep us chasing things outside ourselves. Pascal wasn’t against joy; he just wanted us to stop running from ourselves.

But I also understand that not everyone has the luxury to pause and reflect. A single parent working two jobs can’t just take time off to journal. That’s why empathy matters. Telling people to "just be mindful" without considering their realities can feel dismissive. So maybe it’s not about escaping the hustle entirely, but about finding little moments to reconnect with ourselves.

Our political system doesn't make this easy. We live in a world of soundbites and tribalism. People pick sides, and the loudest voices often drown out the most thoughtful ones. Social media makes everything feel urgent and black-and-white. But life isn’t like that. It's more like a big puzzle. Some people are happy fitting a few pieces together and calling it done. But I believe that if I share gently, piece by piece, others might one day see the full picture too.

Even the way we think about money shows how much we rely on shared stories. Money isn’t real in the same way food or water is. It only works because we all agree it does. The problem is, we often confuse money with fairness. People who have more are seen as better or more deserving, but that’s not always true. History, luck, and policy all play big roles. Economists like Thomas Piketty and Ha-Joon Chang have shown that inequality is built into the system—and it won’t go away just because people work hard.

Different economists offer different solutions. Some say we should borrow to invest in the future (like Keynes), while others say everyone should just fend for themselves (like Sowell). Others, like Chang, argue for rewriting the rules so the game isn’t rigged from the start. But the truth is, no one has all the answers. That’s why we need both personal growth and systemic change.

I once imagined a rebuttal to Kendrick Lamar’s song They Not Like Us. I called mine They Just Like Us. It wasn’t meant to erase differences, but to show how we’re all shaped by similar fears and hopes. Trump, Lamar, me—we all respond to the world in ways that make sense to us. But if we slow down and look closer, we can see that many of our struggles are shared.

So if this reads like the ramblings of a guy who should probably be in therapy—maybe it is. But for me, writing is a way to heal in public. I’m not trying to be right. I’m just trying to be honest. And that, I’ve learned, is harder—and more necessary—than ever.

Respectfully,

Jose Franco

j@stoopjuice.com